Archaeology

The assorted layers of built heritage have remained relatively intact in the Burren uplands due to three main factors. Firstly, the easy availability of building stone in the area meant that existing structures were not exploited to provide new building material. Secondly, the relative durability of stone structures, compared with those made of earth and/or wood. And thirdly, the rocky nature and thin soils of the uplands makes them inherently unsuitable for tillage or reclamation for grassland, largely saving them from a fate that befell many such structures elsewhere. For descriptions of some of the Burren Monuments click here.

Mesolithic

Until recently, little was known about the presence or extent of early Mesolithic settlements in the Burren, as scant evidence from this era has survived. The scarcity of evidence is hardly surprising considering that the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of Mesolithic settlers would probably have supported only a couple of small hunting communities, possibly no more than one or two dozen people, in an area the size of the Burren. However, the discovery and excavation in 2012 of a shell midden (dump) site in Fanore confirmed activity a few generations prior to the arrival of the first farmers in the Burren (c.6,000 years ago).

Neolithic

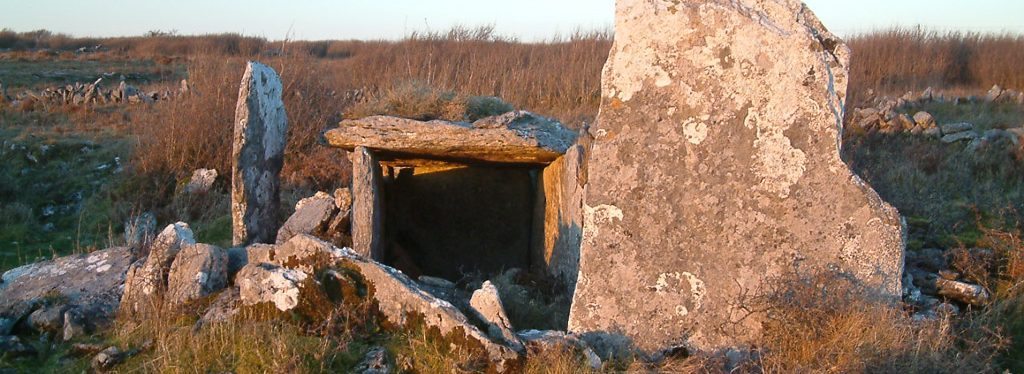

The first farmers are thought to have arrived in the Burren in the early Neolithic period, some 6,000 years ago. Farming activity appears to have been small scale and transient characterised by sporadic clearances, followed by abandonment and subsequent regeneration of woody vegetation. The legacy of these early settlers is best seen in early burial sites such as the famous Poulnabrone portal dolmen, built some 5,800 years ago. The other burial sites found in the Burren associated with this time are court tombs and wedge tombs.

There are two known portal tombs in the Burren: one on the southern periphery at Ballycashin, and the other in the very centre of the Burren at Poulnabrone. Results from an excavation of Poulnabrone reveal that this tomb contained the remains of up to 22 people, interred over six centuries. High levels of stress and physical attrition due to diet and work were noted, as was evidence of injury by a chert arrowhead in one case. Other evidence recovered indicated that these people were farmers of cattle, sheep and goat, and that cereal was also grown.

Wedge tombs occur in a variety of sizes, locations and aggregations in the Burren, and it is thought that they generally date from the late Neolithic. In some places the density of these tombs is so concentrated it suggests the presence of a ‘Megalithic tomb cemetery’.

There are four known court tombs in the Burren, all located along its southern limits. Evidence from Irish court tombs indicates that these structures were not primarily used as funerary monuments, but that they seem to have been a focus of ritual activity over a number of generations.

Bronze Age

Evidence suggests that farming activity and society grew strongly in the Burren over the course of the Bronze Age. There was a major decline in woodland cover and in contrast grassland species were more common, indicating a quite intensive period of farming, one that may eventually have contributed (along with deterioration in climate) to extensive soil loss in the region

This relatively prosperous Bronze Age agricultural society left a significant cultural legacy, including hundreds of cist graves and fulachta fiadha, numerous barrows (earthen and stone), ritual monuments, and several artefacts, including a bronze dagger from Gortaclare near Carran and the famous Glenisheen gold collar.

Though cist graves are less visible on the landscape than the ‘dolmens’ that preceded them, several hundred of the cairns which house these graves have been identified in the Burren, while it is likely that hundreds more have never been recorded.

Iron Age

There was a pronounced decline in agricultural activity over the Iron Age period, which resulted in a significant recovery of secondary woodland, particularly hazel scrub, according to pollen sources. The cause of the ‘Iron Age lull’ in agricultural activity, by no means confined to the Burren, has been attributed to diverse factors such as a downturn in climate, cultural upheaval, and the exhaustion, and in some cases outright loss, of the soil resource.

From a cultural perspective, this was also a time of some upheaval, as the Iron Age is often associated with the arrival of the ‘Celts’. Some of the Burren’s cahers (stone forts) are attributed to the Iron Age such as Cahercommaun or Caherballykingvarga.

One monument type often associated with the Iron Age is the ‘ring barrow’, though a small number of these structures may date from as early as the Neolithic, while many others are of Bronze Age origin. Ring barrows are usually 12-30m in diameter, defined by a ditch with an internal mound (within or underneath which burials are often contained), and/or an external bank.

Some of the few Iron Age artefacts found in the Burren, include pendants, bridle bits and spearheads.

Iron Age artefacts found in the Burren

| Time Period | Dates (approximately) | Monuments (approximately) |

|---|---|---|

| Mesolithic | 9000 – 6000 years ago | Fanore Shell Midden |

| Neolithic | 6000 – 4400 years ago | Portal, Court and Wedge Tombs |

| Bronze Age | 4400 – 2500 years ago | Fulacht Fiadh, Ring Barrows, Cairns (cist graves) |

| Iron Age | 2500 – 1600 years ago | Cahers, Ring Barrows |